Share!

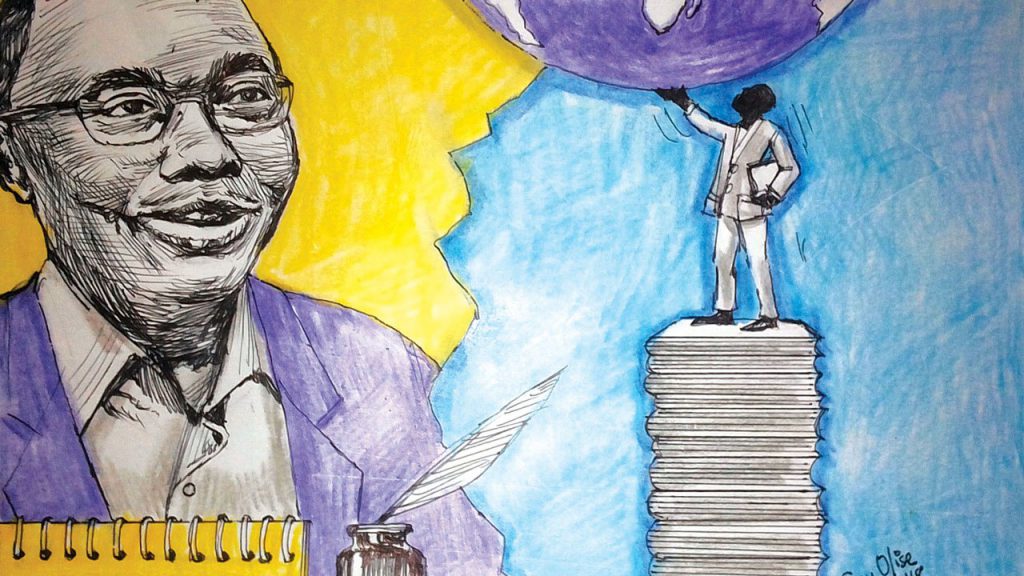

Let me state from the outset, and very urgently indeed, that Tanure Ojaide is an outstanding defining poet, an outstanding defining writer, of our age. I offer this critical opinion not necessarily on account of his prolificacy, as Sunny Awhefeada in a recent essay, ‘’Tanure Ojaide, The Poet-advocate @ 70,” in The Guardian of Sunday, April 29, 2018 (24-25), refreshingly stated, but on account of Ojaide’s rich, varied, revelatory thoughts of uncommon wisdom and candour which make him appealing to all kinds and kinds of readers.

Very recently in Port Harcourt where writers and critics honoured him on his seventieth birthday with a fascinating international conference (May 2-3, 2018) on his “Life, Literature, and the Environment,” which he writes about, one of the two keynote speakers referred to Ojaide as a poet of the Urhobo nation ostensibly because Ojaide is from the Urhobo ethnic group or nationality of our country. I found the label distasteful and poisonous to Ojaide’s literary portrait, poetry and finely crafted works of literature generally. Without disclosing my disappointment and disgust at the label, I asked the keynoter (Professor Harry Garuba of the University of Cape-town, South Africa) why he labelled Ojaide as he had done. I also asked Ojaide if he would in all honesty accept the given label.

Harry Garuba gave an answer I cannot recall. Ojaide himself refused to answer my posed question. But his gold standard silence spoke volumes, which I interpreted to mean that he disagreed with Harry Garuba’s label. Even though he is Urhobo, and a Nigerian, Ojaide is a child, a son, a poet, and a writer of the world. His poetry is the poetry of and for the world. This is why I must reinforce the point that Ojaide is a poet for all kinds and kinds, or, “for all sorts and kinds,” to borrow Robert Frost’s words (Qtd. in Tim Kendall, 48). His poetry, like Robert Frost’s (1874-1963), is poetry for all “potential readers,” as Tim Kendall points out in his study of Robert Frost’s poetic qualities (48). Ojaide’s style may vary from one poem to another but the perceptive critic could see that the poet tries, stylistically speaking, to reconcile his readers (and audiences) even though, again like Robert Frost, he may not feel the “need to address them separately” (Kendall, 48). Ojaide’s udje poems may be poems for his and about his Urhobo people, but that is not to say that readers (and audiences) outside his Urhobo environment and culture may not (or, better stated, cannot) follow or appreciate the art or meanings of the poems. Different readers may find them fascinating from their different angles of readings and interpretations. The point I am trying to make is that Ojaide does not simply yield himself or his poetry to us from the prism and our understanding of the local or national snapshots of subjects and ideas that emblemize the universal and vice versa. And, very importantly, Ojaide writes in English, a fascinating world language which Salman Rushdie has called, rightly or wrongly, “the gold of languages” (ix).

Furthermore, Ojaide’s contemporaries and our fellow scholar-poets such as Niyi Osundare and Ezenwa-Ohaeto, for example, who are indebted to their respective Yoruba oriki and Igbo masquerade poetic practices and traditions cannot be respectively called Yoruba and Igbo poets. They are Nigerians and Nigerian poets, and poets of the world who appropriate their ethnic literature forms and idioms to dwell on subjects outside their ethnic regions. Ojaide must be seen in the same light.

The sentiments I have expressed so far may not go down well with many people – writers and non-writers; critics and non-critics. They may be disappointed with me – rightly or wrongly. My reply to them, in, again, the words of Salman Rushdie, is this: “Literature, we are reminded, is disputed territory” (xii). I am in perfect agreement with Rushdie. As indicated in my title, this essay focuses on Ojaide’s Songs of Myself: Quartet, which was adjudged the second best entry in the LNG “The Nigeria Prize for Literature, 2017” competition. In this volume he seems to be obsessed by the difficulty of locating a point, a place, a centre, a focus, for his poems “for all sorts and kinds,” as already indicated. He tries to solve the problem by calling the poems collectively songs of his poetic consciousness even though they traverse different latitudes and longitudes idea- or subject-wise. To put it, in other words, he tries to solve the problem by framing the poems in his autobiographical consciousness. He wants us to see each of the four parts, which he calls quartets, as lyric autobiography of mini-metaphors of experiences, mini-metaphors of self.

Robert Frost, speaking about how to read a poem, as far back as 1954, posited thus: “A poem is best read in the light of all the other poems ever written. We read A the better to read B (we have to start somewhere; we may get very little out of A). We read B the better to read C, C the better to read D, D the better to go back and get something out of A. Progress is not the aim, but circulation. The thing is to get among the poems where they hold each other apart in their places as the stars do. (Qtd. in Kendall, vi)”

Robert Frost’s theory enunciated above with respect to how to read a poem and get the best out of it in terms of its values and attitudes, and their effect(s) upon the reader and critic, have been and continue to be of value in the res republica of practical criticism and literature generally. To understand a poem better the practical critic may need to read it and another poem that appeared before his or her primary poem of primary focus. The critic may also have to read a poem that appears after his or her primary poem of primary focus. And if the volume or book in which the poem(s) appear(s) is in sections or parts (as Ojaide’s indicates), the critic may need to read and determine how the parts (and poems in each of the parts) logically link one another even “where they hold each other apart.”

Ojaide seems to be in agreement, even if it is not a perfect one, with Robert Frost regarding the latter’s above-quoted extract of theoretical postulation. Ojaide’s own written “Foreword” to Songs of Myself is apropos to cite here:

The four parts of the collection are: “Pulling the thread of the Loom,” “Songs of myself,” “Songs of the Homeland Warriors,” and “Secret Love and Other Poems.”

In the first quartet, the poet assumes the persona of an old man who has experienced much over time and shares his experience of life with others. It ends with advice to youths and speaks on how life has to do with multitasking. In the second quartet, the minstrel presents a persona who mocks himself and in doing so tells us about the society he lives in and its penchant for singling out individuals for criticism. Thus, the poet and his society are simultaneously interrogated in their respective roles in private and public spheres. The third quartet, “Songs of the Homeland Warriors,” has to do with the poet’s Niger Delta experience. While the persona laments ecological and environmental damage and changes, he criticizes not only outsiders that have caused the damage but also his people’s representatives. The concluding quartet, “Secret Love and Other Poems,” starts with an emblematic poem and goes on to deal with the poet’s inner wanderings and thoughts about life. This section also features a variety of poems. The format of the four-part structure affords the poet the opportunity to deal with personal and public experiences in a closely related fashion. (6-7)

This quotation gives us a summary and an understanding of what the poet does or attempts to do in Songs of Myself. I say what the poet attempts to do because each part is not entirely independent of each other as he wants us to believe. Stylistically and thematically, the parts overlap; each part contains poems in which the personality of the poet does not disappear even when he dwells on subjects of “public” concern. The auditory drama of the entire poems in each part reinforces their relatedness and continuity and the artistic mood that created them. And the artistic mood that created the poems is that of the wise, advanced and elderly poet of varied activities and experiences whose subjects in the poems provide a modus operandi for the many shrewd remarks and observations in Songs of Myself.

Let us now consider some of the poems in each of the four parts of Songs of Myself. In our examination of them we will come to the conclusion that Ojaide is a poet “for all sorts and kinds,” which I must reiterate, is what I am primarily concerned with in this enterprise.

One of the poems I love without reservation in the first part of Ojaide’s volume under consideration is “Jolly abandon.” This brief poem of seven stanzas of four lines each ends the section.

The poem lends itself to subjects about companionship/fellowship, bookishness, selfhood, nostalgia, childhood, brotherhood, friendship, communalism, the love of labour, the relationship between man and nature, love of freedom, all of which are subjects that all sorts and kinds of readers will always clamour for and will always yearn to read about. The seven stanzas of the poem focus on these subjects in varying degrees. The poet’s “auditory imagination,” as T.S. Eliot would put it (89), is invigorating: On and on we go crafting the intricate weave of the fishing net as we exchange boisterous banter with fellow fishers and visiting friends.

“We chew savory roasted corn with the season’s jolly abandon even as we weave intently the intricate fishing net. (66)

In these lines Ojaide’s diction is magnificently clear, but it is their auditory charm conveyed in words such as “boisterous banter” and “we chew savory roasted corn” that yields part of my admiration for the poem. The sound the “savory roasted corn” the poet and his companions “chew” as they partake in the rituals of labour is music to the ears – the poet’s, his companions’ and the reader’s. So also is the poet’s and his companions’ “boisterous banter,” which enhances the dramatic appeal of this poem of such warm emotion. The italicized lines of the stanza of the above-quoted extract, reinforces this warm emotion of real bliss in the poet’s consciousness. Furthermore, the italicized lines underscore the rhetoric of limitless childhood-freedom (and its associated connotations), which “the season” endorses and emphasizes to reinforce the relationship between nature and human-beings. Indeed, the poet’s was a childhood, an African childhood, of “jolly abandon.”

In accordance with Robert Frost’s afore-mentioned postulation, I carefully read all the poems that precede “Jolly abandon.” The Ojaide charm is equally evident in them, but the majority of them do not seem to bear the admirable subjects that “Jolly abandon” bears. This may be an astonishing judgment but certainly not an egregious one. Poems such as” Okpara night” (54), “More questions” (55-6), and “Spirit (for Chimalum Nwankwo)” (57) and others will appeal to diverse readers and audiences, at least on account of their descriptive and philosophical lyrics in which he expresses belief in the force of the imagination.

‘Spirit (for Chimalum Nwankwo)” is a paean to friendship. But it may be better enjoyed not in its loyalty to friendship, but in its subjects of magic, myth and nationalism, which define the poet as one whose vision extends beyond his Niger Delta because a poet must always be a poet and remain a poet. Ojaide reinforces this in “More questions,” a poem I will always admire for its concern with ethical issues which the poet illustrates beautifully, in its first part of eight stanzas, with idioms, axioms, aphorisms and paradoxes which derive from his background of a coherent udje culture. The ethical issues, the ethical truths, that is, that Ojaide concerns himself with in the poem are matters of facts contained in the second part of the poem of two-line stanzas:

I hear reports from two contesting sides and know

not which to believe in the gossip frenzy of the day.

Each swears telling me the truth in confidence

but I know that both are lying to score points.

There can be only one truth and it cannot be otherwise;

lies know how to wear diverse constumes to impress.

Only my ears, forced into this courthouse where they must

hear what different advocates will plead to be credible,

suffer the indignity of being insulted as dumb fellows

when in fact they know the truth that is in neither lies. (55-6)

Ojaide, the “old man” of experience, is telling us that gossips and lies are neither good nor profitable, for they will never allow men to live in harmony with one another. His readers of all sorts and kinds should eschew them because they bring discord, and whatever causes discord is wrong and harmful. This is a poem I particularly wish to recommend to every member, staff and students, of our English departments. The above-quoted lines cannot but compel me to recollect the remark I made in a lead paper, ‘’The Inquiry of Literature,” I read on the occasion of the annual conference of the Literary Society of Nigeria which held at the University of Benin, Benin City, Tuesday, November 16 to Friday, November 19, 2010. (It was published in the Journal of the Literary Society of Nigeria (JISN) in 2011). Let me quote myself fully:

I have been overwhelmed by a sense of literature teachers’ and scholars’ moral decay, the social decadence they experience and my own personal feeling of catastrophe, and theirs and my own perceptions of worldly reality.

Intrigues, betrayals, lies, deceits, simulations, hypocrisies, gang-ups, back-stabbing and back-biting, character assassinations, dissembling and all the experts at these wanton vices and more are common, rife and rampant in our Literature Departments. Were Hamlet to visit our Literature Departments he would discover certainly that the State of Denmark was far cleaner, less rotten and less foul than any of them. Year in year out we read and study works of literature (which we also teach others) in the forms of poetry, plays, novels, short stories, autobiographies and biographies in all their different modes and characteristics in the hope of their transforming us and our world. How intriguing are our thoughts and feelings on this score! How intriguing that we dare to examine literature and inquire into how it helps or can help our understanding of the meaning of life! How dare we do so when we have not dared to inquire into how it has aided us to query our conduct as writers, teachers, critics and scholars! Indeed, don’t we have liars, character assassinators, betrayers, dissemblers, plagiarists, adulterers and other persons of despicably questionable attitudes among our tribes of literary practitioners and professionals? How has literature mended, tended and shaped the conduct, perception and general attitudes of such persons among us for their own good and the good of the public, which ultimately ought to advance their own good as well? (98).

The second quartet of the volume is particularly autobiographically interesting, refreshing and stirring. The poems therein are composed, framed, in two-line stanzas all through. They also are exceedingly axiomatic, idiomatic, aphoristic and paradoxical. They are brilliant songs of self, which are both passionate and intellectual. They illustrate Ojaide’s personality as a poet of myriad voices, who sing in several personae. The reconciliation of his passion(s) and intellect is effected, made possible, by symbolic and metaphorical representation of the wisdom of the inspired Romantic and lyrical poet in a manner that is esoteric despite the reality depicted in some of the poems.

“Everything is a metaphor” (68-9), which opens this quartet, contains its “vision:” to the minstrel everything is a metaphor. (69).

He itemizes his themes in a manner that is tantalizingly esoteric because he does not pare his images. Readers and critics of all sorts and kinds who cherish abstraction rather than exactness of expression will find Ojaide a spell-binder. This quality of his is discernible in other poems in the other quartets, but it is in the second quartet that it is most predominant. His recondite style protects him against attack from those he attacks. In this wise he follows the tradition of Urhobo udje satirists who compose their mocking songs in metaphors and symbols as contrivances to prevent injuries from those they ridicule: …‘’even the brave fear a battle”(67). This, however, is not to suggest that all the second quartet poems present Ojaide’s ideas reconditely. The poem “The emigrant” is relevant to cite here:

Because I was a coward scared to death by the blood of money-making rituals I fled the land of inescapable culture; because I didn’t want to rob or kidnap centenarians and babies for ransom, I ran away not to be poor and disgrace my family; because I did not want the National Assembly to be the pinnacle of my career I flew out for another life. (98)

“The emigrant” is essentially a poem of the public sphere even though it “critically” focuses on the “sins” of the poet who lists some of the ills of his society, ills that forced him out of his land into exile. Some of these ills which depict the true state of the poet’s land (which is also our land) are captured succinctly in the quoted lines above.

“The emigrant” is beautifully transparent enough, for the poet uses common words which firmly link the poem to reality, the reality it captures. Very early in the poem, the poet queries those who blame him for emigrating: I am not the first senior child to emigrate nor will be the last; our great grandparents founded Oshogbo over a century ago.

It befuddles me, the outcry about my stay in town; it was not enough

my parents crossed the Ethiope here and I am a permanent immigrant; it befuddles me because robbers and murderers are conferred with chieftaincy titles; no song against theft from the commonwealth.” (98).

Here we see the conflict between good and evil. The good son of the land who emigrates for good reasons does not understand why his people deride him when “robbers and murderers are conferred with chieftaincy titles.” The ethics of the ruling class “befuddles” him. But there is something very significant in the poem that the reader must not gloss over. It is the story, the history, of emigration from Urhobo-land. The poet’s Urhobo ancestors emigrated to Oshogbo (in Yoruba-land), which, according to the poet, his ancestors founded. Is this a realistic contention that is based on a factual historical account, or, is the poet just exercising his imagination to deride his deriders?

No related posts.